Abstract

Cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P)—a condition associated with speech, hearing, feeding, and dental problems, as well as anomalies of the bone and soft tissue around the mouth—is a common birth defect around the globe. The prevalence of this condition varies widely across different countries and regions, and is apparently highest among Asians and lowest among Africans. A review of literature reveals that there exists a dearth of information on experiences of parents of children with CL/P and stigma communication, as well as cultural beliefs associated with CL/P in Africa. To fill this gap, we conducted a descriptive qualitative study examining the experiences of parents of children with CL/P, stigma communication, and cultural beliefs associated with CL/P in Kenya. Twenty four in-depth interviews were done involving purposefully sampled parents of children born with CL/P at AIC CURE International Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. Five overarching themes emerged under the lived experiences of parents of children with CL/P: Emotional experiences; relational experiences; burden of care and concerns; reaction by the public and friends; and source of social support. The stigma messages and beliefs associated with CL/P further exacerbated the stigma. The study revealed that stigma communication associated with CL/P remains a significant source of social and psychological anguish to parents and guardians of children with CL/P. These findings have critical implications for the management of stigma communication associated with CL/P. They point to the need for public awareness campaigns on CL/P to demystify the condition, its causes and treatment. The study shows that raising public awareness of CL/P would go a long way towards addressing the stigma associated with the condition. It underscores the need for open communication and engagement with all stakeholders to manage stigma communication associated with CL/P through culturally appropriate anti-stigma campaigns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital anomalies are a major public health concern worldwide because of their contribution to infant and childhood mortality, chronic illness, and disability (ICBDSR, 2014). A study by Conway et al. (2015) notes that orofacial clefting is the most common congenital malformation with a worldwide birth prevalence of 1/700 live births. Orofacial clefting prevalence, according to Conway, varies with regions and is highest in Asian countries (1/500), intermediate in Caucasians (1/1000), and lowest in African populations (1/2500). Further, Conway et al. observed that clefts of the lip have a 2:1 male to female ratio, while clefts of the palate have a 1:2 male to female ratio. Clefts of the lip are more commonly unilateral than bilateral and favor the left side. For all ethnicities together, approximately 50% of all clefts are combined clefts of the lip and palate, 25 to 35% involve the lip only, and isolated CP accounting for approximately 25% (Gundlach and Christina, 2006; Moosey and Little, 2002).

Zeytinoğlu et al. (2017) noted that CL/P refers to a phenomenon where the entire upper lip is divided at birth, which can continue up into the nose through the nostril and into the incisive foramen (hard palate immediately behind the incisor teeth). Clefts are classified as unilateral or bilateral based on whether they are located on one or both sides of the cleft lip and/or palate (roof of the mouth). Cleft lip palate involves a gap in both the lip and palate (Friedman et al., 2010). While scientists cannot pinpoint the cause for the development of CL/P, various studies have shown that chromosomes, genes, advanced maternal age, proteins, and the environment, as well as spontaneous genetic mutation all play a role in the development of CL/P in utero (Zeytinoğlu et al., 2017).

Largely, CL/P is associated with speech, hearing, feeding, and dental issues, as well as irregularities of the bone and soft tissue that may require surgical reconstruction for the affected children. Some babies born with CL/P will need ongoing surgical, dental, and speech treatment, which can affect their quality of life (Zeytinoglu and Davey, 2012). In addition, some school-age children will experience learning disabilities, poor self-concept, social anxiety, and social stigma from peers—and consequently may need additional psychosocial support (Berger and Dalton, 2009; Kramer et al., 2007).

A sizeable number of researchers have focused on children affected by this condition, and it has long been recognized that parents and caregivers also experience psychosocial issues (Berger and Dalton, 2009; Kramer et al., 2007). However, most of these studies on parental experiences have been primarily cross-sectional, quantitative, and focused on the emotional, social, and care experiences of mothers and mainly from high-income countries (HIC) (Hlongwa and Rispel, 2018). Further, Hlongwa and Rispel note that in high-income countries, studies have found that parents experienced varying degrees of shock, anger, denial, distress and anxiety, and a sense of “loss of control” over a CL/P birth (Ingstrup et al., 2013; Johansson and Ringsberg, 2004). In addition, in these studies from high-income countries, parents underscored the importance of appropriate and accurate information about CL/P and health and social support with their children’s condition at birth (Johansson and Ringsberg, 2004).

According to Conway, et al. (2015), the stigma of an unrepaired orofacial cleft greatly alters a child’s ability to integrate into the social and cultural environment. Beyond the esthetic deformity, orofacial clefts are given a wide variety of meanings and consequences in different cultures. In regards to etiology, some groups view clefts to be due to divine will, evil spirits, handling sharp objects during an eclipse, or even a husband fishing during the pregnancy (Ross, 2007). Among Nigerian societies, it is sometimes viewed as divine punishment for parental sins such as witchcraft or prostitution, and the children born with CL/P are therefore kept away from the public (Fadeyibi et al., 2012). Many of these misconceptions affix blame to parents and families, further isolating the child within their own family and community, and complicating access to complete medical and surgical care.

Kenyans, like Nigerians and many African people, are largely made up of collective cultures and religious people who often resort to cultural beliefs to explain many stigmatized health conditions (Kimotho, 2018). Review of literature indicates that there is a paucity of research on experiences of parents of children with CL/P, stigma communication, and cultural beliefs associated with CL/P among Kenyan communities—and especially studies of parents that would be representative of urban and rural settings. This is the scholarly gap that this study set out to address. To respond to this gap, and acquire an in-depth understanding of the lived experiences of parents or guardians living with children affected by CL/P formed, this study was guided by three research questions (RQs):

RQ 1: What are the lived experiences of guardians or parents living with children affected by CL/P among Kenyan communities??

RQ 2: What is the nature of the components of stigma messages associated with CL/P among Kenyan communities?

RQ 3: What are the cultural beliefs associated with CL/P among Kenyan communities?

Theoretical framework

Stigma is typically a social process, experienced or anticipated, characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame or devaluation that result from experience, perception or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgment about a person or group (Scheyett, 2005). Although there are some clear indicators of the social origins of stigmatization and the factors that perpetuate it, a generally accepted unitary theory of the origins of stigma remains elusive to date. Goffman and Goffman (1963) seminal work, Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, originally published in 1963, remains one of the most foundational works in helping scholars come up with a coherent framework of understanding stigma. Goffman’s theory of stigma states that individuals are categorized by the society on the basis of the anticipated normative values—separating the “normal” from the “deviants.” Stigma, according to Goffman, refers to an attribute that is profoundly degrading, reducing the individual who possesses a particular trait from a whole to an aspersed and discredited one (Goffman and Goffman, 1963), and consequently the person is socially degraded. The gist of this approach is the understanding that stigma arises during a social interaction.

Goffman’s work approaches the study of stigma from a social constructionist perspective. Social constructionism is a philosophical assumption underlying this study and has its ontological roots in the symbolic interactionism tradition. Theorists from the symbolic interactionism tradition believe that the meanings of social objects, such as people and actions, are social constructs. Social constructionists hold as their cardinal assumption that in a society, people jointly construct their understanding of phenomena in their world and meanings are developed during social interaction. Some of these social constructions used to perpetuate stigma among the members of different communities include: Myths, cultural beliefs, stereotypes, and misconceptions associated with a health condition (Kimotho and Miller, 2016; Link and Phelan, 2001; Pescosolido et al., 2008).

By defining stigma as a spoiled identity, which means that a person is somehow not normal or accepted by society because of a physical disability, signs of “immoral” or non-conforming behavior, or membership to a particular group, Goffman cast stigma as a social construction in which society determines which statuses deserve to be stigmatized (Smith, 2007). As such, the creation and maintenance of stigmatizing beliefs and stereotypes about CL/P would be represented in the language, as well as the labels used to describe persons with CL/P. Therefore, stigma is the process whereby society negatively defines a particular mark such as CL/P as “…an attribute that is deeply discrediting…” (Goffman and Goffman, 1963, p. 3). In other words, at its most basic level, stigma, from a social constructionist point of view, is a powerful discrediting and sullying social label that radically alters the way individuals view themselves and are viewed by others as persons. Goffman’s work underscores the importance of the process of communication in the creation and maintenance of stigma.

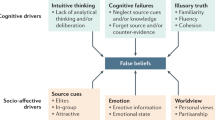

Understanding stigma communication as social constructions expressed through language is a critical starting point in understanding the nature of stigma communication associated with CL/P. Specifically, stigma communication can be defined as the mechanism through which CL/P stigma messages are created, reinforced and maintained through a communication process and how such messages spread through communities to teach their members to recognize the disgraced (i.e., recognizing stigmata) and to react accordingly (Smith, 2007). Stigma communication theory argues that stigma messages are constituted of mark, label, responsibility and peril.

Marks, as described by Smith (2007), are imputes (for example skin color, blindness, or cleft of the lips) or deviant behaviors (prostitution) used to pick out an individual within a stigmatized group. A label refers to a name made to distinguish the stigmatized as a different social entity. The label not only draws attention to the group’s stigma but also stresses “them” as different and separate from “us” and aids in distinguishing the marked from the “normals.” Responsibility points to the argument that those in the stigmatized group (or their next of kin) are to blame for the choices they made. Peril is the information that connects the stigmatized individuals to a physical or social danger jeopardizing the community’s way of life. Peril is a constant reminder to the community members to avoid the stigmatized.

Understanding the nature of any stigma phenomenon needs a clear grasp of the lived experiences of persons who deal with such stigma every day. In this case, parents of children with CL/P deal with what Goffman called courtesy stigma (stigma by association). People who bear a courtesy stigma are those regarded by others as having a spoiled identity because they share some form of affiliation with the stigmatized persons (Goffman and Goffman, 1963). Several studies suggest that stigmatization, discrimination, and sociocultural inequalities are common “phenomena” experienced by parents and guardians of children with CL/P (Adeyemo et al., 2016; Zeytinoğlu et al., 2017). According to Fink and Neave (2005), the human face is a corridor of emotions, a gateway to verbal and nonverbal communication, and a criterion for social acceptance and mate selection. The esthetics of facial structure are used by humans to measure not only one’s beauty but also his or her personality, intelligence, social class, trustworthiness, social skill, popularity, and overall “goodness” (Langlois et al., 2000). Congenital facial impairments remain a source of social and mental distress to many affected families. CL/P is particularly distressing to the guardians or parents of affected children mainly because of its particular location in the orofacial region. Many guardians or parents usually feel ashamed/ uncomfortable with bringing out their children in public (Adeyemo et al., 2016).

CL/P in Kenya

Cleft lip and palate is a significant congenital malformation in Kenya. Among African populations, Kenya reports 1.7/1000 live births, while Ethiopia reports 0.2/1000, Nigeria 0.5/1000, and Uganda 0.8/1000 (Hlongwa et al., 2019). Further, it is estimated that between 600 to 700 corrective surgeries are done in Kenya annually (Waweru, 2019). When corrective surgery for CL/P is performed in major hospitals in Kenya, it may cost between 500 USD to 2500 USD (Sheriff et al., 2018). Such a high cost often exclude the poor and marginalized communities in Kenya. However, these collective surgeries are sometimes offered in various public and private hospitals in Kenya in partnership with governments, hospitals and non-governmental organizations. Some of the non-governmental organizations that have continued to offer corrective surgeries in Kenya include Operation Smile, Smile Train, Help a Child Face Tomorrow, and Cleft-Kinder-Hilfe among others.

AIC-CURE International Hospital is one of the renowned hospital in East Africa for its role in providing corrective surgeries to children with CL/P from poor communities for free. AIC-CURE International Hospital is in Kijabe, a town located 60 km north-west of Nairobi City, in the sub-county of Lari, Kiambu County. It provides care for children suffering from a wide range of acquired or congenital conditions. AIC-CURE International Hospital was preferred for this study because it offers free corrective surgery to children from all parts of the country which would provide diversity in data on stigma and beliefs associated with CL/P.

Methodology

The study employed a descriptive research design, using a qualitative research approach to describe lived experiences of such parents; this enabled study of the nature of stigma communication associated with CL/P and cultural beliefs associated with the condition among Kenyan communities. A qualitative approach was deemed appropriate for the study because it facilitated in-depth understanding of the issues surrounding CL/P stigma, and allowed for flexibility to respond to unexpected and new development in the data (Marshall and Rossman, 2014).

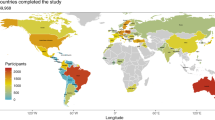

Data was collected using in-depth interviews with 24 purposefully sampled respondents recruited during a CL/P medical event that took place from July 23–26, 2019 at AIC CURE International Hospital in Kijabe, Kenya. Initially we targeted twelve in-depth interviews (the recommended standard figure by various qualitative scholars including Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). However, following Creswell and Poth (2016) and Nascimento et al. (2018) advice, data collection continued till a point of saturation was achieved. Data collection reached saturation at the 17th respondent, but interviews continued until the 24th respondent, when it became clear that no new themes were emerging from the data. Data collection is considered saturated when no new elements are found and the addition of new information ceases to be necessary, since it does not alter the comprehension of the researched phenomenon. It is a criterion that enables the establishment of the validity of a data set (Nascimento et al., 2018).

During the event, parents and caregivers brought their children to the hospital for corrective treatment. A purposive and convenience approach to sampling was used to recruit the respondents. The specific inclusion criteria for the qualitative in-depth interviews was as follows: (a) the respondent needed to be the biological parents or a guardian of a child diagnosed with CL/P. This criterion was considered essential as parents/guardian are expected to be very close to the children and would be most probable victims of stigmatization; (b) the respondent needed to be aged 18 years and older; and (c) parents or guardians must be willing to discuss issues to do with stigma and cultural beliefs associated with CL/P. These two criteria were in line with the requirements by the ethical bodies mentioned elsewhere in this paper. The exclusion criteria included the following: (a) the presence of a cognitive or physical disability that would impair the parents’ ability to complete interviews, and (b) children who might have been previously diagnosed with other significant health problems (e.g., heart problems), in addition to the CL/P. These criteria were considered important for the purpose of assuring consistency, quality and credibility of the data collected (Creswell and Poth, 2016).

Detailed memos were done during the whole data collection period to help the team track thematic saturation. The interviewers thoroughly explained to the respondents the intent of the interview and the purpose of the study. All the respondents were provided with written informed consent, at the beginning of the interview session, to sign. Permission to audio-record was requested before commencement of the interviews. All interviews were audio-taped, and then later transcribed verbatim.

To capture the personal experiences of the parents of children with CL/P, the following interview questions guided the discussions: (i) What was your first reaction when the doctors told you about the condition of your child or when you saw the baby? (ii) Whom did you talk to first about the cleft? (iii) Did you or your spouse have difficulties accepting the condition of your baby, and if so how did you overcome that challenge? (iv) How did this experience impact your relationship? (v) What has been some of the biggest challenge for you living with your child with this condition? (vi) How has this condition changed the way you feel or think about yourself? (vii) How has this condition changed the way you look at life in general? (viii) What has helped you through this period in your life? (Where do you get your social support from? What kind of support?).

To capture some aspects stigma communication and cultural beliefs associated with CL/P, the following interview questions guided the discussions. (i) How do other people react when they see your child? (Probe for blame of parent for the condition by the society). (ii) What stories exist in your communities about the cause of CL/P? Or what do people attribute as the cause of CL/P? (iii) What cultural beliefs do you know from your community that are associated with CL/P? (iv) What in your opinion are some of the misconceptions held widely about CL/P? (v) How has the condition of your child affected your social life? (Probe: For example, do you go out for social functions? Explain please. (Probe for self-exclusion from social occasions, interaction with friends etc.). (vi) Are there labels that people tend to use on children or persons who have CL/P? (vii) Is there anything else that you think we should know about your experience?

Interviews lasted 30–45 min. Besides taking short notes during the interview, the interviewer also noted any relevant expressions that could not be captured on the audiotape (e.g., tone of voice, facial expression, and body language). The interviews were all transcribed verbatim and coded as qualitative data. The coding process was informed by the Saldaña coding system (Saldaña, 2016). The transcripts of all the respondents were given pseudonyms to ensure complete anonymity.

Credibility, transferability, dependability, conformability, and trustworthiness

The following strategies were used to increase creditability, transferability, dependability, conformability, and trustworthiness (Creswell and Creswell, 2017): (a) triangulation, (b) peer debriefing, and (c) inquiry audit. Findings were triangulated through the use of multiple coders. The coders then held meetings to compare the outcomes; where inconsistences were noted, they were discussed and resolved through consensus. Lincoln and Guba (1985) defined peer debriefing as explaining the research process to a disinterested peer who can explore and challenge a researcher’s biases, meanings, and explanations. The de-briefer challenges the researcher about his or her hypotheses, encouraging deeper exploration and for planning the next steps. In this descriptive qualitative study, the de-briefer was another faculty member who is an expert in qualitative approach.

Credibility may be sufficient for ensuring dependability (Lincoln and Guba, 1985); however, there are other techniques that could increase dependability of findings—like inquiry audit. Inquiry audit technique was used for this study. Auditors (First author and a graduate assistant) examined the research process and findings to assure its accuracy. An inquiry audit is not possible without an audit trail. An audit trail is a technique for establishing conformability and describes how records are kept during each step of data collection and analysis. For this study, these records included: (a) raw data of the interviews, (b) field notes, (c) data reduction and analysis trails, (d) reflexive memos, (e) notes describing the trustworthiness process, and (f) notes describing the theoretical frameworks (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board clearance of the United States International University—Africa was sought and obtained. In addition, this study was approved by AIC CURE International Hospital Research Board, and permission granted for data collection. We adhered to best practice standard and ethical procedures—which included voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, and anonymity in the management of data and reporting of study findings.

Findings

The purpose of this study was to examine the experiences of parents of children with CL/P; and further describe the stigma communication and cultural beliefs associated with CL/P. This section will give a description of the participants, detailed report of the findings and illustrations to support these findings.

A total of 24 participants were interviewed. The participants were drawn from regions of the country. The majority of the participants came from central Kenya, followed by Rift Valley and Nairobi (Table 1). Majority of the participants were female constituting 91%. At least 10 (47%) of the participants were married, 8 (33%) were either separated or divorced while 6 (25%) were still single.

Data analysis entailed two major cycles of coding as described by Miles et al. (2014). The first cycle of coding entailed the researchers immersing themselves into the raw data and carefully reading through and reflecting on it. During this cycle data condensation was done and this enabled the researchers to retrieve the most meaningful data, to assemble chunks of data that go together, and to further condense the bulk into readily analyzable units.

In the second cycle, provisional coding strategy was used help the author cluster the codes into more meaningful themes. Miles et al. (2014) argue that provisional coding strategy allows the qualitative researcher to draw tentative codes relevant to their studies from the theoretical framework or from the reviewed literature to form the initial framework for analysis. In this study provisional coding strategy was guided by the reviewed relevant literature, including (Adeyemo et al., 2016; Hsieh et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2012; Wanjeri and Wachira, 2009) and mainly informed how themes were named. To come up with the final list of themes provisional codes were revised, modified, some deleted, or expanded to include new codes depending on the information emerging from the data. The next section presents the findings of this study in details.

Experiences and perceptions of parents of children with CL/P

After conducting thematic content analysis, five overarching themes (as illustrated in Table 2) emerged: Emotional experiences of having a child with CL/P; relational experiences; burden of care and concerns; reaction by public and friends; and source of social support.

Emotional experiences of having a child with CL/P

In almost all the cases with the respondents interviewed, getting a child with CL/P elicited diverse emotional reactions from the parents. These emotional reactions included shock or surprise, stress, fear, self-blame, acceptance of the baby or rejection of the baby, shame, and even suicidal and homicidal thoughts.

Most mothers narrated how they went through distressful and anxious moments as they tried get to terms with the reality of delivering a child with CL/P as demonstrated in the following excerpts:

It was a depressing experience; I really cried. I was shocked because I had not seen such a child in my community before. (Respondent 11)

After birth, the baby was crying a lot. She looked strange. Her mouth had split in the middle and was always wide open and as she cried she looked really strange. I kept on wondering if she was really a human being. I had not heard about or seen a condition like this in my life. (Respondent 14)

To most of the parents, the moment they held their babies or saw them for the first time was stressful and terrifying, and many resulted to self-blame as they sought to understand the cause of the condition. They believed that they were to blame, perhaps because they were not keen to adhere to the prenatal clinics or because they had been using contraceptives before conceiving the baby born with CL/P:

I believe I am to blame for this condition since I did not go for the clinic during the pregnancy; this could be the cause. (Respondent 10)

Sometimes, I wonder if there is something I did wrong. Sometimes I wonder if it was the family planning contraceptives that may have caused this and I don’t use them anymore now. (Respondent 24)

In some cases, respondents reported instances where the shock, fear and anxiety culminated in ultimate rejection of the babies born with CL/P by their fathers as described in the excerpts below:

…When my husband came to see the baby, he looked at the child and was shocked. He looked anxious and angry. He shook his head and rejected the child. He said that the child was not his and he did not look like him. The senior doctors at the hospital tried to talk to him but he still looked discontented and angry. He just left the premises without even talking to me. (Respondent 2)

The father of my child said that that was not his son, despite the fact that he resembles him a lot. He said he doesn’t give birth to “walemavu” (disabled children). (Respondent 24)

In some cases, upon realizing that they had a baby with CL/P condition, some parents contemplated either to commit suicide or kill the baby. Some parents had clear homicidal ideations on how they could actually kill the baby, as demonstrated below:

When I saw the baby I was frustrated. I wanted to throw myself from a certain high cliff, while carrying her on my back, so that she could die or both of us die. But I went back home and encouraged myself. My husband was not aware. (Respondent 19)

My husband was very shocked too. After seeing the baby for the first time, he said he had not seen anything like that before. He even once suggesting if it was possible to have the baby strangled. (Respondent 16)

Burden of care and concerns

Burden of care and related concerns was another major theme that emerged from the data collected form the parents of children with CL/P. The theme had four subthemes: Difficulties in feeding the baby; financial strain; need for constant attention; schooling; speech development. All the respondents constantly described the various challenges they encountered while feeding the children. To many of them, this was the most challenging thing to handle in caring for children with CL/P. Many mothers’ frustration came from the fact that the baby couldn’t suckle or hold on to the nipples. According to the data, mothers resorted to expressing milk and feeding the child with a spoon. The frustrations of most new mothers of children with CL/P is well captured by the following excerpt:

One of the most frustrating challenges for me was feeding my baby. My baby kept on crying and I could not help her—I was really stressed. I wondered how the child would be feeding and suckling. The baby could not hold on to the nipple. The child lost weight so much. She had 4 kg and she dropped to 3 kg within days. She used to cry a lot and this depressed my heart … to a point I felt like I could throw away the child and leave my home. (Respondent 7)

Besides difficulties in feeding children with CL/P, other concerns raised by the respondents were: The need for constant attention; schooling; speech development; and financial strain. Many mothers explained that they had to quit their daily jobs to attend to children born with CL/P. This constant need for attention and special care made many respondents get concerned about the future schooling prospects of their children with CL/P, as evidenced in the following excerpt:

A major challenge is that this baby is fully dependent on me and I cannot leave this child with somebody else. Therefore, I cannot go to work like other mothers. (Respondent 12)

In addition, most respondents described financial constraints as a major challenge for parents with children with CL/P. According to most of the respondents, the child needed special powdered milk and constant medical attention, which was way above what they could afford.

…The doctor advised me to buy the Nestle Nan powdered milk, but the milk was too expensive… I had to buy two cans in a week. That really stressed me… I knew I needed money, a lot of money, so that the child could be treated. But I did not have this kind of money. (Respondent 4)

Relational experiences

Relational experiences formed the third major theme that emerged from the interviews. This theme mainly captured relationship-based experiences, particularly on how a parent’s relationship with others was impacted by having a child with CL/P. It emerged that having a child with CL/P had many adverse consequences on the relationship between the parents of children with CL/P and other members of the community. Sub-themes from this theme included isolation; strained marital relationship; divorce or separation; and rejection by extended family and friends.

Many of the parents interviewed during this study reported instances of isolation. They were mainly in two forms—isolation by members of the community and friends, and self-isolation. Either form of isolation had some emotional effects on the affected parents, as demonstrated in the excerpts below.

People from my community distanced themselves from us. I was only left with the father of the baby and one sympathetic neighbour. (Respondent 12)

My baby’s condition has significantly affected my social life—especially going to church. I no longer go to church. I no longer visit my friends either. I don’t go to public places because people will ask questions. As you can see, it is obvious she can’t breastfeed, so carrying all those stuff to feed her is a bit cumbersome. Sometimes I feel like I will be a bother to people. So I just stay at home. (Respondent 13)

In some cases as reported by the respondents, the birth of a child with CL/P resulted in a strained marital relationship, divorce or separation. The following excerpts illustrate this point:

My relationship with my husband was really impacted by this condition… he had difficulties accepting this condition. He was in denial and resented us… he would come to visit me but he would not talk to me… then he would leave silently and not tell me. He didn’t want anything to do with him, he would just go and it seemed like I had given birth to a disabled child, something that seemed to deeply offend him. (Respondent 2)

My husband blamed me for the child’s condition. As we speak, we have separated because of this baby. I am leaving at my parent’s home. We had to separate because he looked at our son’s condition as a disability, although the doctor had told us the condition was temporal, and the boy would be fine after a surgery. (Respondent 9)

In some cases, the mothers of children with CL/P condition would not only get divorced but also rejected by family members and friends because of their babies’ condition, as these respondents narrate in the following excerpts:

My husband’s family members did not want me or the child back in their home because they thought it would be a burden to them and it would probably ruin their public image. They wondered how people would perceive the condition and they are well known in their area. They felt that the child would be a profound mark of shame… they did not want to be known in the community as that “family with a disabled child”. (Respondent 2)

Reaction by public and friends

From the data, it emerged that the parents of children suffering from CL/P were concerned about two major things: People gossiping and talking ill about the baby, and staring at their babies, as illustrated in the excerpt below:

I don’t like the way people stare and gossip about my baby. They do not say the things when we are together but they say things when they go away. (Respondent 10)

People talk a lot of bad things about my baby. When I pass around carrying my baby people just stare a lot at my kid. Kids would stop playing by the roadside to stare at him and ask what happened to him all the time. (Respondent 24).

Yes, I feared the stories people used to talk about your child and I didn’t want people to visit me either. Because they would later spread rumours after seeing my baby. These kind of rumour really stressed me (Respondent 8).

Source of social support

Finally, the theme of source of social support was almost always intertwined in the narrative of the parents’ lived experiences. There were two major sources of social support, according to the data that was collected during this study: The family and the church:

My family used to encourage me; they used to call me and assured me that all will be well with the child. They would even bring me stuff and that made me happy. My sister used to come to our home and we would encourage each other. That kind of support made me forget all. (Respondent 2)

I can say our church has helped me the most… with money and information, until I was able to come all the way to this place. (Respondent 5)

Nature of the components of stigma messages associated with CL/P

In this section, the findings on the nature of the stigma communication messages associated with CL/P are presented. SMC framework was used to describe the four categories of messages (marks, responsibility, label and peril) (Smith, 2007).

Marks

The marks that identify persons with CL/P in the communities represented by the respondents were consistent with symptoms described elsewhere in this paper. In a nutshell, marks that characterize CL/P include a divided upper lip, which may continue up into the nose through the nostril and into the incisive foramen (hard palate immediately behind the incisor teeth).

Responsibility

Responsibility refers to how blame for the stigmatized condition is apportioned to the stigmatized group (or their next of kin). Two themes emerged from the data on responsibility: Blame by others; and self-blame. Most of the respondents reported being blamed by other members of their communities or close family members for the CL/P condition as demonstrated in the excerpts below:

People blamed me for the condition of my baby. Some people told me that I had sold my child to the devil and that I had joined a cult of devil worshippers. (Respondent 12)

My husband blamed me for the child’s condition… He seemed to deeply believe that I was responsible for the condition of our son. It is as if I had done something bad to our son that caused the condition. (Respondent 2)

Instances of respondents blaming themselves for the condition of their babies were notable. Many seemed convinced that the condition of their babies was as a result of something they did or didn’t do when they were pregnant.

Sometimes, I wonder if there is something wrong that I did that could have caused this. Sometimes I think it was the family planning contraceptives I used before conceiving this baby that caused this problem. I don’t use them anymore now… (Respondent 24)

I believe I am to blame for this condition since I did not go for the clinic during the pregnancy; this could be the cause. (Respondent 10)

Labels

Labels refer to the names of references that given to the stigmatized persons. In most cases and as it emerged from the data, persons with CL/P were referred to as “mlemavu”. Mlemavu is a term drawn from the Kiswahili language largely spoken in eastern Africa, which means “a disabled person”. Another Kiswahili label that emerged from the data is “kiwete”, which still means “a disabled person” (this term is considered impolite among Kiswahili speakers).

Another lady came to my house and told me to take the kiwete (disabled) baby to my husband… I felt like crying but I told God to give me strength. (Respondent 24)

We had to separate because he looked at our mlemavu (disabled) and his condition as a real ulemavu (disability), although the doctor had told us the condition was temporal, and the boy would be fine after a surgery. (Respondent 2)

Peril

Perils are stigma messages that connect the stigmatized person to a physical or social danger jeopardizing the community’s way of life. In this case, the persons affected by CL/P were children and therefore, no physical dangers were anticipated or reported by the respondents. However, it emerged from the data that children with CL/P were often associated with bad omen or evil spirits, and thus were seen as carriers of evil spells. Members of the community would limit their interaction with such children out of fear of getting the evil spell:

People would just stare at him from a distance. They would never want to get close to my baby. Some believed that the baby was possessed by some evil spirit…or he is an ill omen. They believed touching him would make bad things happen to them. (Respondent 1)

Cultural beliefs associated with CL/P in Africa

Five major beliefs on the cause of CL/P emerged from the data: curses, evil spirits, inherited condition, God’s will, and trauma from natural phenomena. The most prominent beliefs among the communities represented in this study are that CL/P is an inherited condition. In almost all the cases, mothers and their relatives tended to probe if cases of CL/P existed among the relatives.

My mum believed that it could be from the family of my husband. She once asked me if this condition existed in my husband’s family and this really irritated me. (Respondent 10)

The other most common belief was that CL/P was caused by shock or trauma from natural phenomena like lightning, thunderbolt, or an earthquake:

People from my community believe that this condition is caused by shock… like from lightning or thunderbolt when one is pregnant, so the baby is shocked or terrified when she is very small and this makes the lips and mouth to crack. (Respondent 14)

They say that if you get shocked while pregnant… like in a situation where there are earthquakes and people are shocked, the child may get cracks in the mouth. (Respondent 2)

A few of the respondents attributed the CL/P condition to curses and evil spirits, while others said that it was “God’s will”, as illustrated by thee excerpts:

People around our village believe that there was something wrong with our family…we had a curse… (Respondent 5).

I believe this condition is part of God’s will. God planned it to be that way. (Respondent 14)

Discussion

This study set out to examine the experiences of parents of children with CL/P: The stigma communication messages and beliefs associated with CL/P. In this study, most parents (mothers and fathers) reported experiencing shock and stress when they first learnt that they had a child with CL/P. In several cases, the situation was further exacerbated by the rejection of the babies by the fathers or family members. In almost all the cases where the fathers rejected the babies born with CL/P, they expressed disappointment and blamed the mother for bringing forth a child with CL/P. It was apparent from the data that stigma associated with CL/P was often extended to parents or guardians. This observation is not unique to this study. Hlongwa and Rispel (2018) had made a similar observation in their study on caregivers’ perceptions of healthcare provision and support for children born with cleft lip and palate.

Stigma is what follows when society degrades the status of a person due to some unique attributes that are socially deemed as undesirable. When such stigma is extended to other people, it is called courtesy stigma (stigma by association). The finding indicates that courtesy stigma leads to a number of unprecedented outcomes among the parents of children with CL/P. Many of them lived in fear of social judgment, or being blamed for bringing forth a child many perceived as mlemavu (disabled). As Adeyemo et al. (2016) have observed, stigma as a social process is not only characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame or devaluation, but also perception or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgment. Anticipation for adverse social judgment is based on an enduring feature of identity conferred by a CL/P condition. In this case, it emerged that many communities represented in this study consider persons with CL/P as disabled. Persons living with disability in many parts of Africa endure a lot of social stigma, discrimination and exclusion. The scenario described here explains the root of anxiety, fear, and unprecedented decisions—like rejection of the babies born with CL/P by their fathers, and homicidal or suicidal ideations—which were reported in this study. Intense stress and stigma associated with CL/P have been reported previously as factors that could lead to parents contemplating suicide or killing their babies who had CL/P (Berger and Dalton, 2009; Mcheik et al., 2006; Turner et al., 1998).

Stigma and stigma communication—how stigma messages are created, reinforced and managed through a communication process—had a lot of implications on how the stigmatized persons associated or related with others in the society. As such, describing the lived experiences of the parents of children with CL/P included expounding on how the stigma associated with the condition affected their relationships with various members of the communities. Largely, it emerged that most mothers ended up in a strained relationship, divorce or separation, rejection by friends and family members, or self-isolation. The findings of this study corroborate the study by Umweni and Okeigbemen, which showed that the birth of a child with CL/P had adverse effects on its parents and that the effects are often greater on mothers (Beaumont, 2006; Umweni and Okeigbemen, 2009).

On the nature of the stigma messages associated with CL/P, the findings of this study largely support Smith’s theory of stigma communication (Smith, 2011). Smith’s theory suggests that understanding the components of stigma messages (mark, label, responsibility, and peril) is essential to a conceptualization of the nature of stigma communication. However, in this study, “label” seemed to be a weak factor in the creation or sustenance of stigma associated with CL/P. There was no specific reference or linguistic label for CL/P that was reported by the respondents. “Mlemavu”, a more general Kiswahili term which refers to a disabled person, was used as a label for children with CL/P by the respondents. These findings depart from previous research on stigma communication that had clear illness-specific labels reported—for instance, labels for leprosy, tungiasis, and mental illness (Kimotho, 2018; Kimotho et al., 2015; Ritchie et al., 2010). However, the use of the label “mlemavu” (disabled) was perceived to be stigmatizing, demeaning, and one that effectively discredited the whole person as disabled despite the fact that the CL/P affects the area around the mouth and the condition is correctable through surgery.

Cultural beliefs about curses from ancestors or parents—and beliefs that attributed the illness to evil spirits—were common among the respondents’ narratives. These beliefs promoted fear and anxiety among the community members, leading to social exclusion of the stigmatized persons with CL/P and their guardians/parents. As argued elsewhere, curses in African communities are taken seriously and it is assumed they don’t just happen. So, if community members believe the health condition is attributable to a curse, what they mean is that the “cursed person” is also condemned (Wakanyi–Kahindi, 2012). There is a widely-acknowledged belief among African communities that people don’t just get cursed without reason. Rather, they are cursed because they violated the community’s norms at some point in their lives. Therefore, a curse is perceived by the society as a punishment (Kimotho et al., 2015). When a community perceives a health condition as “deserved punishment” for violating cultural norms, it is less empathetic with that condition or the affected persons. These findings, therefore, corroborate previous studies that argue that cultural beliefs about a health condition or an illness could lead to prejudice and social exclusion of the stigmatized persons (Abdullah and Brown, 2011; Kimotho, 2018). Cultural beliefs among the collective cultures play a significant role in the stigma communication process.

Conclusions and recommendation

This study has highlighted the experiences of parents regarding CL/P, in particular the nature of stigma messages and the beliefs associated with CL/P among African communities living in Kenya. According to the findings, stigma communication associated with CL/P remains a significant source of social and psychological torture to parents and guardians of children with CL/P. The study findings have critical implications for the management of stigma communication associated with CL/P. Our findings point to the need for public awareness campaigns on CL/P to demystify the condition, its causes and treatment. Raising public awareness of CL/P would go a long way in addressing the stigma associated with the condition.

The mothers gave heart-rending accounts of stress and frustration emanating from the burden of caring for a child with cleft lip and palate, especially feeding difficulties and the need for constant care before surgery. Coupled with courtesy stigma from the community, many parents went through depressing moments—and some parents contemplated suicide or had clear homicidal ideations on how they could actually kill the baby. As such, there is a need to sensitize parents of children with CL/P about the guidelines that exist on feeding approaches, advice, information, and the management of complications. As Hlongwa and Rispel (2018) recommend, these guidelines could be adapted both for parents and health professionals outside specialized health facilities.

This study, however had some limitations that need to be highlighted. The most obvious limitation was the research approach used: qualitative approach. Consequently, a small sample was considered and in depth interviews were used to collect data on the experiences of the parents, as well as stigma and beliefs associated with CL/P. While the findings of this study provide in-depth understanding of the phenomena, they are not generalizable. Therefore, further research in this area may include a quantitative study to investigate if the various components of stigma influence health seeking behaviors of the parents of children with CL/P. Children with CL/P need constant medical attention and as such, these parents constantly make decision on whether to take them hospital or not.

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in this article. The datasets analyzed during this study are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/5PFELF.

References

Abdullah T, Brown TL (2011) Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: an integrative review. Clin Psych Rev 31(6):934–948

Adeyemo WL, James O, Butali A (2016) Cleft lip and palate: parental experiences of stigma, discrimination, and social/structural inequalities. Ann Max Surg 6(2):195

Beaumont D (2006) Exploring parental reactions to the diagnosis of cleft lip and palate. Paed Nurs 18(3):14

Berger ZE, Dalton LJ (2009) Coping with a cleft: psychosocial adjustment of adolescents with a cleft lip and palate and their parents. Cleft Palate-Cran J 46(4):435–443

Conway JC, Taub PJ, Kling R, Oberoi K, Doucette J, Jabs EW (2015) Ten-year experience of more than 35,000 orofacial clefts in Africa. BMC Pediatr 15(1):8

Creswell, JW, Poth CN (2016) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications

Creswell, JW, Creswell, JD (2017) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches: Sage publications

Fadeyibi IO, Coker OA, Zacchariah MP, Fasawe A, Ademiluyi SA (2012) Psychosocial effects of cleft lip and palate on Nigerians: the Ikeja-Lagos experience. J Plastic Surg Hand Surg 46(1):13–18

Fink B, Neave N (2005) The biology of facial beauty. Int J Cosmetic Sci 27(6):317–325

Friedman O, Wang T, Milczuk H (2010) Cleft lip and palate. Cummings otolaryngology: head and neck surgery, 5th edn. Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia

Gundlach KK, Christina M (2006) Epidemiological studies on the frequency of clefts in Europe and world-wide. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg 34:1–2

Goffman I, Goffman E (1963) Stigma; Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall

Hlongwa P, Rispel LC (2018) “People look and ask lots of questions”: caregivers’ perceptions of healthcare provision and support for children born with cleft lip and palate. BMC Public Health 18(1):506

Hlongwa P, Levin J, Rispel LC (2019) Epidemiology and clinical profile of individuals with cleft lip and palate utilising specialised academic treatment centres in South Africa. PloS one 14(5):e0215931. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215931

Hsieh Y-T, Chao Y-MY, Shiao JS-C (2013) A qualitative study of psychosocial factors affecting expecting mothers who choose to continue a cleft lip and/or palate pregnancy to term. J Nurs Res 21(1):1–9

ICBDSR, W. (2014) Birth defects surveillance a manual for programme managers. World Health Organization, Geneva

Ingstrup KG, Liang H, Olsen J, Nohr E, Bech B, Wu C, Li J (2013) Maternal bereavement in the antenatal period and oral cleft in the offspring. Human Reprod 28(4):1092–1099

Johansson B, Ringsberg KC (2004) Parents’ experiences of having a child with cleft lip and palate. J Adv Nurs 47(2):165–173

Kimotho SG (2018) Understanding the Nature of Stigma Communication Associated With Mental Illness in Africa: a Focus on Cultural Beliefs and Stereotypes Deconstructing Stigma in Mental Health. IGI Global, pp. 20–41

Kimotho SG, Miller A (2016) Stigmatizing beliefs, stereotypes and communication surrounding tungiasis in Kenya

Kimotho SG, Miller AN, Ngure P (2015) Managing communication surrounding tungiasis stigma in Kenya. Communicatio 41(4):523–542

Kramer F-J, Baethge C, Sinikovic B, Schliephake H (2007) An analysis of quality of life in 130 families having small children with cleft lip/palate using the impact on family scale. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Surg 36(12):1146–1152

Langlois JH, Kalakanis L, Rubenstein AJ, Larson A, Hallam M, Smoot M (2000) Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bullet 126(3):390

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Establishing trustworthiness. Nat Inquiry 289:331

Link BG, Phelan JC (2001) Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol 27(1):363–385

Marshall C, Rossman GB (2014) Designing qualitative research. Sage Publications

Mcheik JN, Sfalli P, Bondonny JM, Levard G (2006) Early repair for infants with cleft lip and nose. Int J Ped Otorhin 70(10):1785–1790

Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J (2014) Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. SAGE Publications

Moosey, P, Little, J (2002) Epidemiology of oral clefts: An international perspective. In: Wyszynski, DF (Ed.), Cleft lip and palate: From origin to treatment. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Nascimento LDCN, Souza TVD, Oliveira ICDS et al. (2018) Theoretical saturation in qualitative research: an experience report in interview with schoolchildren. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 71(1):228–233

Nelson P, Glenny AM, Kirk S, Caress AL (2012) Parents’ experiences of caring for a child with a cleft lip and/or palate: a review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev 38(1):6–20

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Dickinson WB, Leech NL, Zoran AG (2009) A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 8(3):1–21

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Lang A, Olafsdottir S (2008) Rethinking theoretical approaches to stigma: a framework integrating normative influences on stigma (FINIS). Soc Sci Med 67(3):431–440

Ritchie D, Amos A, Martin C (2010) “But it just has that sort of feel about it, a leper”—Stigma, smoke-free Zeytinoglu legislation and public health. Nic Tob Res 12(6):622–629

Ross E (2007) A tale of two systems: Beliefs and practices of South African Muslim and Hindu traditional healers regarding cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J 44(6):642–648

Saldaña, J (2016) The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, London: SAGE

Sheriff S, Zawahrah HJ, Chang LV et al. (2018) What is the cost of free cleft surgery in the middle east? World J Surg 42(5):1239–1247

Scheyett A (2005) The mark of madness: Stigma, serious mental illnesses and social work. Social Work in Mental Health 3(4):79–97

Smith RA (2011) Stigma, communication, and health. The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication. Routledge, London, p 480–493

Smith RA (2007) Language of the lost: an explication of stigma communication. Commun Theory 17(4):462–485

Turner SR, Rumsey N, Sandy J (1998) Psychological aspects of cleft lip and palate. Eur J Orthod 20(4):407–415

Umweni A, Okeigbemen S (2009) Gender issues in parenting cleft lip and palate babies in southern Nigeria: a study of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital. Early Child Dev Care 179(1):81–86

Wakanyi-Kahindi L (2012) The Agikuyu concept of THAHU and its bearing on the biblical concept of sin

Wanjeri JK, Wachira JM (2009) Cleft lip and palate: a descriptive comparative, retrospective, and prospective study of patients with cleft deformities managed at 2 hospitals in Kenya. J Craniofac Surg 20(5):1352–1355

Waweru M (2019) Nairobi Hospital Inspires Hope For Cleft Lip and Palate Cases.

Zeytinoglu S, Davey MP (2012) It’s a privilege to smile: impact of cleft lip palate on families. Fam Syst Health 30(3):265

Zeytinoğlu S, Davey MP, Crerand C, Fisher K, Akyil Y (2017) Experiences of couples caring for a child born with cleft lip and/or palate: Impact of the timing of diagnosis. J. Marital Fam. Ther 43(1):82–99

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the AIC CURE International Hospital Ethics and Research Board for granting approval for this study and the publication of the results obtained from it. Further, the authors would wish to thank all the respondents and their families, and the staff of AIC CURE International Hospital who assisted us during this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kimotho, S.G., Macharia, F.N. Social stigma and cultural beliefs associated with cleft lip and/or palate: parental perceptions of their experience in Kenya. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 181 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00677-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00677-7